Some thoughts on climate crisis in [cli-fi] films

a blog post by ASTRID BRACKE, PHD in Holland

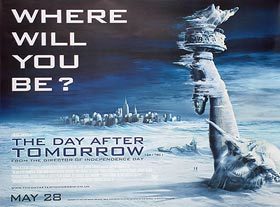

Love that tagline

I recently saw the 2017 cli-fi film Geostorm. The premise of the film is that in the near future a solution is devised by scientists to control the freak weather caused by climate change. The solution is a network of satellites colloquially called ‘Dutch boy’, after the story of the Dutch boy who put his finger in a dyke to stop a flood.* It costs a lot of money but, the voice-over tells us, it brings the world together and keeps climate crisis in check. Problem solved.

While this premise is probably enough to merit Rotten Tomatoes’ review of Geostorm as “a disaster of a movie”, the way in which climate change is framed in the film made me think. For instance, it demonstrates a point I make in my recent book: anthropogenic climate change has become firmly lodged in our cultural awareness. We no longer need an explicit explanation in order to link the events happening at the beginning of the film to climate change. In 2017 this was much more the case than ten or fifteen years ago. As my partner (who suffered through Geostorm with me) pointed out, in The Day After Tomorrow (2014) the fact that climate change is causing the freak weather had to be made much more explicitly.

Geostorm‘s language about climate change also stands out. As the voice-over tells us, “we fought back”. Climate change is a villain, and the hero is the scientist who developed ‘Dutch boy’. Appropriately, an article in The Guardian that appeared around the release of Geostorm asks whether climate change is Hollywood’s new supervillain.

What Lawrence Buell calls the ‘David-and-Goliath’-trope has long been a part of the environmental movement (1). It is usually used in relation to pollution, when big corporations are the Goliath (as in the environmental classic Silent Spring, for example) and ordinary people or misunderstood scientists are the David. This us-versus-them dichotomy is not unproblematic, though, as Buell also notes. In the case of the production and use of pesticides critiqued in Silent Spring, for instance, it absolves the consumer of any blame. The same happens in Geostorm: the causes of climate change are glossed over, and what matters is that a solution is provided and that “we fought back”.

Geostorm also replicates the kind of first world exceptionalism so common in many Hollywood films – and in the real world. The film’s ending reveals that the devious secretary of state aimed to use “Dutch boy” to destroy all of the former enemies of the US. He wants to bring the political balance back to what is was in 1945, with the US as superpower.

High deathtoll, but still plenty of exceptionalism..

The Day After Tomorrow, probably the best known film about climate crisis, makes a slightly different point. At the end of the film, when the heroes have been saved and reunited, the President makes a televised speech. He mentions that the US and other first world countries have now come become “guests in nations we once called the Third World”. There’s plenty of exceptionalism in this film as well of course, not the least because after having first decided to abandon half the country to the massive snowstorms, helicopters are sent out to rescue our hero, his son and others who have miraculously survived in New York. Nonetheless, while Geostorm magnifies climate crisis inequality in favour of the US, The Day After Tomorrow suggests that climate crisis might alter this inequality. Climate crisis, it seems, would be beneficial to the global balance of power.

Quite a bit of research has been done on The Day After Tomorrow as a climate film. The results vary from suggesting that the film had a bigger effect on people’s awareness of

climate crisis than the IPCC reports, to suggestions that it didn’t really have an effect at all. A 2009 paper notes that The Day After Tomorrow increased “information seeking behaviour” amongst viewers. Other audience studies had different results: in the UK the film made viewers anxious, and although they may have seemed more willing to do something about climate crisis, they didn’t know what. In Germany, viewers of the film came to the conclusion that climate change would not affect them personally. The Day After Tomorrow is also perhaps a bit too much of a Hollywood-disaster-film to really invite serious reflections on climate crisis (even though one of the first casualties of the freak weather hitting the US is the Hollywood sign, blasted away by a tornado) (2).

It’s become a platitude, but representing climate crisis in film or in novels is hard. I do think it is important that literature and film address climate crisis, if only because the crisis itself, as well as our awareness of it, has become so much a part of our society. The problem with films such as The Day After Tomorrow (and especially Geostorm) is, as Michael Svoboda puts it, that

the apocalyptic film also disconnects viewers’ current lives from the possible future depicted on the screen

That is to say: I like thinking about how these films, and novels, depict climate crisis. It fascinates me how stories are created that shape how we think, imagine and talk about climate crisis. I think it is important that we study these stories and point out patterns, and problematic aspects. But I also don’t want to fall into the trap of prescriptiveness: there’s more to a novel than its ‘message’, just as a film should also be entertaining.

*As a Dutch person, I feel like I should point out here that the story of the boy with his finger in the dyke is largely unfamiliar to Dutch people (it’s an American story). Also that it’s just too weird, as anyone living near water knows.

Notes:

1. Lawrence Buell discusses this in Writing for an Endangered World (2004).

2. A really good overview of climate crisis in film is provided by Michael Svoboda, in “Cli-fi on the screen(s): patterns in the representation of climate change in fictional films” (2016).

No comments:

Post a Comment