The Buzz about Maja Lunde and Norwegian ‘Cli-Fi’

Recent years have seen novelists everywhere tackle the burning issue of climate change but in Norway environmental concerns have long been the focus of literary invention. Here British literary critic Boyd Tonkin explores how Norwegian authors have tried to save the world ....one story at a time.

A few years ago, I sat outside on a golden summer afternoon and watched the warm sun dance over waters of a brilliant blue. The Mediterranean? Far from it. I was in Tromsø, 350 km north of the Arctic Circle, and the improbably mild home of the world’s most northerly botanic garden. Crucially, that balmy (and, of course, endless) summer day was not in itself some alarming freak event. True, warmer temperatures have made recent winters shorter and wetter. But the blessings of the Gulf Stream have always given Tromsø, with its ice-free port, a climate that defies expectations for a city perched near our planet’s roof, at almost 70 degrees north. In fact, much of Norway – for all its winter storms and snows – enjoys weather that, in the gentler seasons anyway, mocks its high latitudes to welcome and nurture human settlement.

It’s no surprise that this delicate balance between harshness and mildness, ice and sun, white and green, should leave deep traces on the nation’s art and literature. Or that the pursuit of inspiration from the natural world should underpin the quintessentially Norwegian ideal of friluftsliv, the outdoors life. Or, indeed, that the mortal threat to this hard-won equilibrium posed by accelerating climate change should now preoccupy many of the nation’s authors. In Norway, as elsewhere, speculative fiction about climate change and its consequences (“cli-fi”, as critics have dubbed it) has ceased to be a marginal genre of interest to activists alone.

The international success of Maja Lunde, the Norwegian writer whose eco-themed novels have sold in millions and found translations all around the world, has made her work a flagship for the anxieties and dilemmas that haunt writers and readers today. An overheating planet, rising seas, melting ice-caps, mass extinctions, the failure of waters and crops, refugees in flight from shortages and conflicts: the crises of climatic change feel so profound that they may both ignite and overwhelm the imagination. How to create plausible stories that measure up to these epic, and tragic, upheavals without falling into the reader-repelling traps of the tract, the sermon, the finger-wagging prophecy of doom? For Lunde herself (as she told Amy Brady of the Yale Climate Connections site this year), the secret is to keep things human, dramatic and particular: “My writing starts with feelings. Never with a message. I think about the story and the characters; I want to be true to them, to feel that they are alive.”

Extreme climatic events have helped shape literary art since ancient times. Historians surmise, for instance, that the freak seasons of the mid-17th century fed the freezing, and burning, horrors that fill John Milton’s Paradise Lost. Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein in 1816, the “year without a summer” after volcanic ash from Mount Tambora in Indonesia had darkened the world’s skies. Science fiction and fantastic literature of the mid-20th century – in works such as JG Ballard’s The Drowned World and The Burning World – vividly imagined an increasingly uninhabitable Earth, decades before the science of greenhouse emissions had become common knowledge. Then, as the millennium turned, fresh understanding gave an urgent edge to dystopian speculation in novels such as Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy.

Knut Faldbakken, the Norwegian author of several early climate change novels published in the 1970s (Photo: Gyldendal Norsk Forlag)

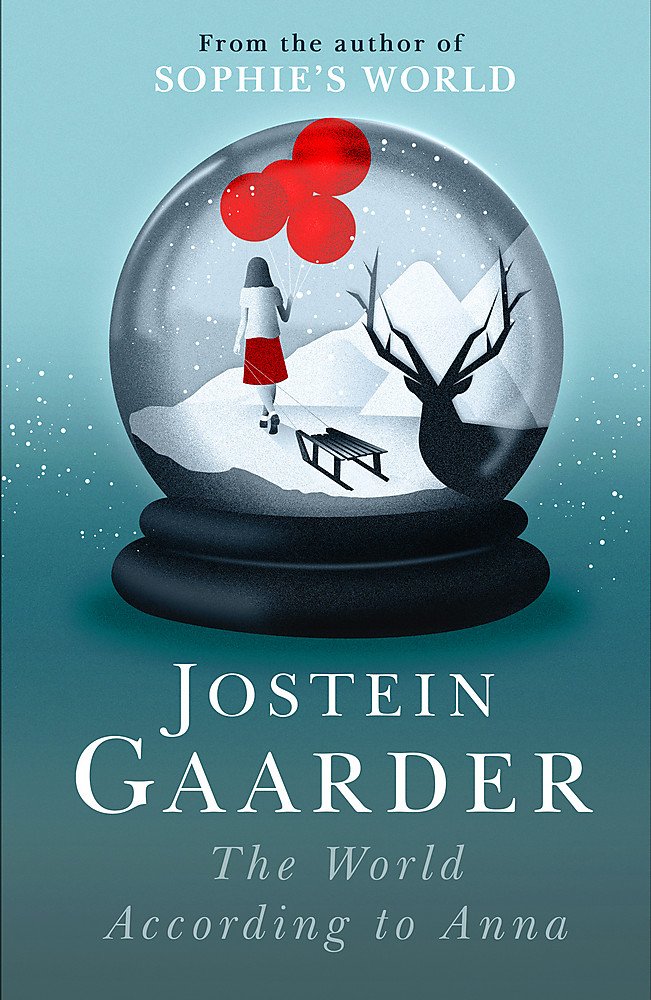

Later fictional responses to environmental menace span genres as diverse as the sensational airport thriller (Gerd Nygårdshaug’s Chimera, 2011), the mystical quest for redemption in the wake of disaster (Berit Ellingsen’s Not Dark Yet, 2015), and the futuristic fable aimed at young readers (Jostein Gaarder’s The World According to Anna, 2015). Gaarder’s teenage heroine, Anna foresees the calamities in store for a scorched, parched Earth. Her messenger from the wasteland of 2082, Nora angrily demands – in the wake-up-call tones that often sound through these books – “I want the world that you had at my age”. Norway has also drawn writers from outside (notably Ian McEwan’s Solar, 2010, which is partly set in Svalbard).

Of course, much of Norwegian “cli-fi” shares the methods and ideas of eco-aware authors from other lands. However, aspects of the national culture colour these books with local shades of green. Knowledge of global warming has, in some sense, enhanced the collective self-image of a “lucky country”– one whose position and prospects might make it a magnet for refugees from hotter, drier places as its fresh waters, forestry and agriculture survive warming better than in lower latitudes. (There’s no lack of dystopian warnings either: of flooded shorelines, melting glaciers, even the demise of skiing as the snows retreat.)

Meanwhile, Norway’s ascent to the rank of global oil-and-gas power – while cleaner hydroelectric plants supply its own domestic needs – has prompted soul-searching in literature, as in politics. Can a nation grow rich by exporting fossil fuels while lamenting their local and global impacts? In The End of the Ocean, the second of Maja Lunde’s climate novels, her eco-warrior Signe casts a withering eye over “all those who are constructing Norway… while simultaneously they are destroying the world”.

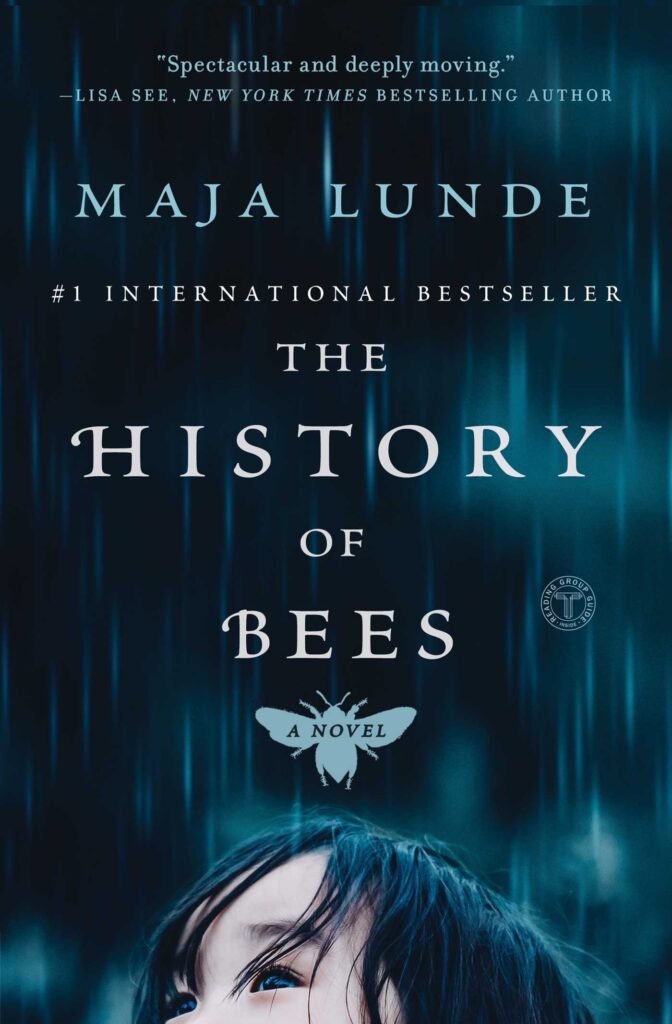

All these currents merge in Lunde’s fiction. The Oslo-based writer was known for children’s fiction before The History of Bees, the first part of a planned “Climate Quartet”, became a bestseller at home and abroad. Three of these four novels have so far appeared: The History of Bees (2015), The End of the Ocean (2017), both translated by Diane Oatley and published by Scribner, and, in 2019, Przewalski’s Horse. The History of Bees skilfully guides the reader through the insects’ critical place in the natural cycles that support human life, as it switches between stories set in mid-19th century England, the 2000s in the American Mid-West, and a wrecked, near-starving future China in 2098. Attitudes to nature, past and present, are shown to have paved the path towards environmental hell.

In Lunde’s fiction, the healthy balance represented by bees – and their traditional keepers – gives way to catastrophic disruptions, hastened by toxic agribusiness and an altered climate. We see how the bees’ “meticulous and peaceful work, systematic, instinctive, hereditary” keeps us all alive and fed. In this dystopian scenario, “colony collapse” leads by 2045 to the bees’ extinction. However, she also sounds a modest note of hope – a key seasoning for “cli-fi” if authors want to steer their readers out of paralysing despair.

Sogn og Fjordane in Vestland, the spectacular setting for Maja Lunde’s The End of the Ocean (Photo: Coastal Museum, Sogne og Fjordane)

Again, Lunde leaves some wriggle-room for hope, not just in her plot-twists but through the resilience and idealism of her characters – above all the indomitable Signe.

The younger Signe fumes that “the pragmatic human being doesn’t understand passion” as her idealism collides with vested interests and the simple yearning for an easy life. Lunde’s novels show that passion has its part to play in denouncing, and averting, catastrophe. But so too, she hints, does scientific reason. The intellectual armoury that pushed humanity towards climate-change disaster may help it to find an exit as well.

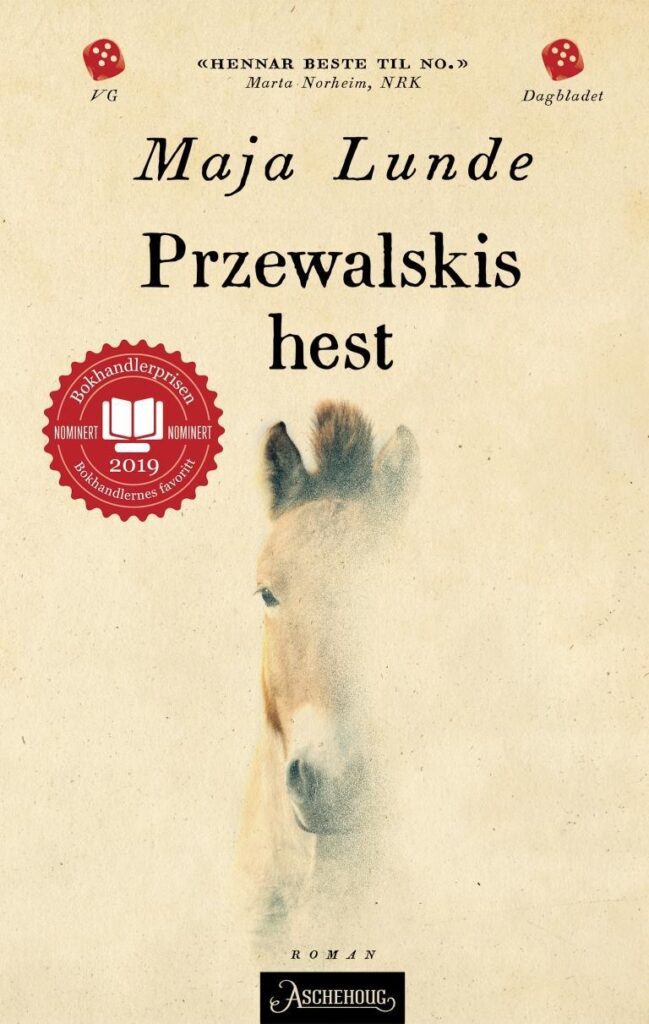

Lunde’s latest book, Przewalski’s Horse, turns its gaze towards humanity’s relationship with animals. Via another triple time-frame, it interrogates the roles of science, activism and – vitally – compassion in healing our broken connections with nature.

As with other Norwegian climate-change visionaries and speculators, Lunde’s job is not to find comprehensive answers but to ask the right questions using the fiction-writers’ own toolbox of imagination, insight and empathy. “While reports and journalism talk to our heads, fiction talks to our hearts,” she has said. “And to be willing to change, to do what is needed, I think we need deep engagement, we need our feelings.” If that deep engagement bears fruit, then our descendants might be able to sit out in the summer sun of Tromsø and still feel that all is right with the world.

Maja Lunde’s novels are published in Britain by Simon & Schuster

The World According to Anna by Jostein Gaarder is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson

Knut Faldbakken’s novels in translation are out of print but rare editions can be found at Abebooks

Details of the Arctic Alpine Botanical Garden at Trømso can be found at Visit Trømso

Top photo: cover detail from the Norwegian edition of The History of Bees (published by Aschehoug)

No comments:

Post a Comment